Corporate Cannabis: One-Hitter or Here to Stay?

Note: Julia Justusson wrote this post, which was originally published on the ktMINE blog. Republished here with the author's permission.

This is the second installment in ktMINE's Cannabis series. In Part I, it discussed the marijuana IP landscape in general and explored trademarks in the industry. In this post, it investigates the potential movement of Big Pharma and multinational agricultural corporations into the cannabis space.

Patents as Indicators of Corporate Priorities

Patent data can provide a useful indicator of activity across a wide variety of industries. Here, we examine the patent portfolios of several major corporations rumored to be entering the cannabis game.

Monsanto

Monsanto first introduced genetically modified pesticide-resistant soybean seeds in the United States back in 1994. Since then, it has grown and now produces at least a third of the United States’ corn and soy crops.

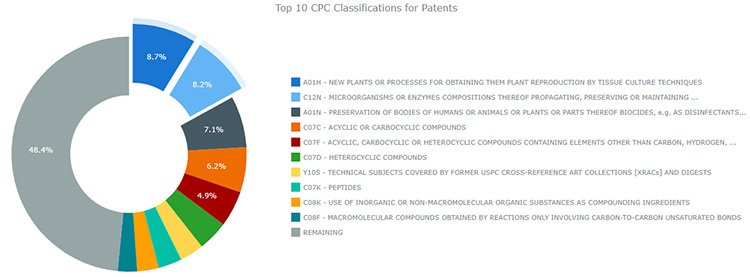

Fifteen percent of Monsanto’s patents, when looked at over all time, fall under the Cooperative Patent Classification codes (or CPC codes) C12N, Microorganisms or enzymes compositions thereof, and A01H, New plants or processes for obtaining them. According to Eric Podlogar, market lead of IP strategy and valuation at ktMINE, CPC codes are critical when comparing patent portfolios. While the quality of these classifications is still improving, CPCs alongside supplemental analysis can provide a useful indication of companies’ priorities and main areas of technological development.

When we narrow our search to include only patents published within the last five years, nearly 30% of Monsanto’s patents fall under the A01H New plants or processes … category. This suggests a shift in Monsanto’s priorities and an even stronger emphasis on plant-related R&D and IP activities.

Patenting cannabis plants or parts of the plant is a sticky situation, although not impossible. The U.S. government holds a utility patent on some nonpsychoactive compounds derived from the marijuana plant. A plant patent is slightly different. The Canna Law Blog explains the two:

In particular, whereas a plant patent has only a single claim that defines the scope of the patent, a utility patent can have multiple claims, each addressing different parts of the plant or ways of using the plant that are disclosed in the specification of the patent.… IP protection for cannabis plants used to be theoretical, but this changed recently. In the last two years, the PTO has issued plant patents, e.g., U.S. PP27475 P2 (Cannabis Plant Named "Ecuadorian Sativa"), and utility patents, e.g., U.S. 9,095,554 (Breeding, Production, Processing, and Use of Specialty Cannabis).

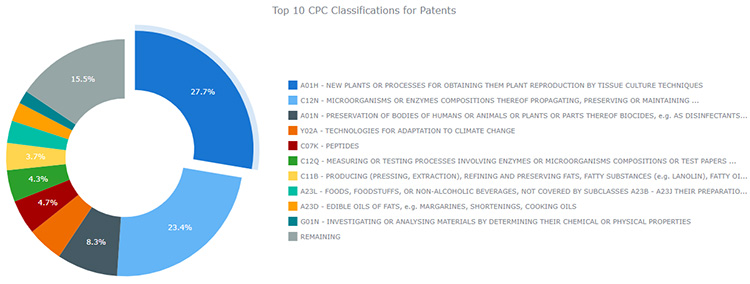

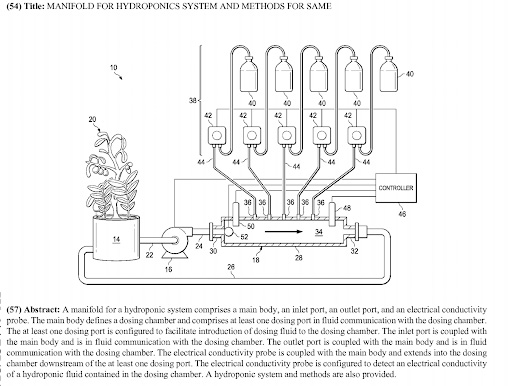

According to Statista in cooperation with New Frontier Data, 44% of cannabis-related patents filed in the United States between 1976 and 2017 fell into the “plant biology” category, with 25% in the “medical/pharmaceutical” category and the remaining share of patents split between other categories including testing/process method and new product formulation.

Source: Statista

Source: Statista

Scotts Miracle-Gro

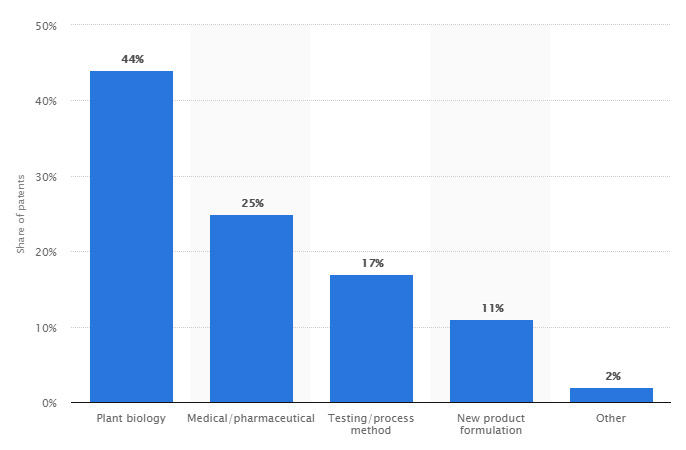

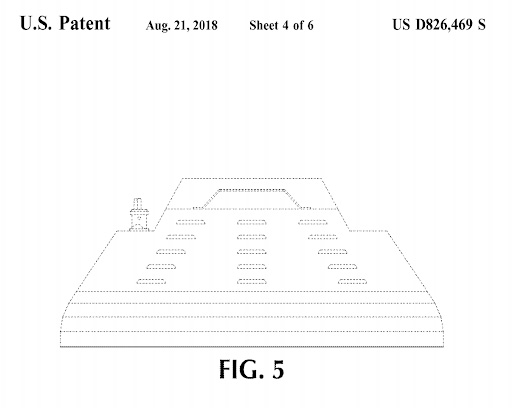

Scotts Miracle-Gro, a company known for its fertilizers, grass seed, and dirt, has recently been granted a number of patents related to hydroponics and indoor plant growing systems. These include Manifold for hydroponics system and methods for same and Horticulture grow light, as shown below.

Source: ktMINE patent database; image from patent full-text document on Espacenet

Jim Hagedorn, the CEO of Scotts, has publicly expressed his belief that marijuana is the “biggest thing” in the lawn and garden business. “We’re talking dirt, fertilizer, pesticides, growing systems, lights.” These statements align with the above patents found through a search for Scotts Miracle-Gro in ktMINE’s database.

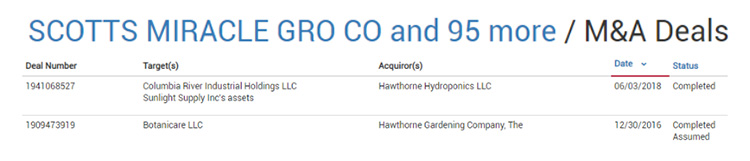

Scotts has also acquired several hydroponics companies in the past few years, including Sunlight Supply and Botanicare.

Source: KtMINE Company Profile/M&A Deals. Hawthorne Hydroponics LLC is a known subsidiary of Scott's Miracle-Gro.

GW Pharmaceuticals

GW Pharma is the top owner of cannabis-related granted patents. It owns 5% of the total of these patents, with the next top company holding less than half that amount, around 2.4%.

Studies of Epidiolex, a plant-derived CBD medication, have shown that it significantly decreases the frequency of drop seizures in adults and children with certain types of epilepsy. Greenwich Biosciences, a U.S.-based subsidiary of GW Pharma, produces Epidiolex. Just over a quarter—26.4%—of the patents GW Pharma holds mention “epilepsy,” which makes sense given that GW Pharma’s Epidiolex product is the first and only FDA-approved pharmaceutical formulation derived from the marijuana plant.

In addition to epilepsy, GW Pharma’s patents include a variety of pharmaceutical applications of cannabis-derived compounds, from treatment of neuropathic pain, brain cancer, and schizophrenia to topical remedies for inflammatory skin diseases.

Sativex, a GW Pharma product used as treatment for symptoms of multiple sclerosis, was the first cannabis-based medication to be licensed in the U.K. Bayer markets Sativex in the United Kingdom and Canada, but it is not currently approved for use in the United States. The ktMINE agreements database contains a full-text license and distribution agreement indicating that Bayer and GW first partnered as early as 2003, although Sativex was not available in the U.K. until 2010 despite GW’s hopes for early approval.

Source: ktMINE IP Platform.

Source: ktMINE IP Platform contains millions of patents and assignments. Click image for publicly available full-text agreement.

Bayer is commonly thought of as a pharmaceutical company, but it is managed as a life science company with three divisions: Consumer Health, Crop Science, and Pharmaceuticals. Its Crop Sciences division invests more in research and development than any other company in the agricultural industry.

Big Agriculture Meets Big Pharma

Earlier this year, Bayer acquired Monsanto. As mentioned above, Bayer has a partnership with GW Pharmaceuticals, with Bayer holding exclusive rights to market GW’s cannabis-based Sativex product in the U.K. and Canada.

Michael Straumeitis, founder of a hydroponics nutrients company, has stated that the connections between Monsanto, Bayer, GW Pharmaceuticals, and Scotts Miracle-Gro spell serious trouble for the future of cannabis. He believes Bayer and Monsanto will utilize genetically modified marijuana crops to effect a “corporate takeover of the marijuana industry,” with the aim of forcing consumers who want to use cannabinoids to “get a doctor’s prescription and buy marijuana compounds from corporations.”

The threat of Monsanto developing GMO marijuana was a widely circulated (and extensively debunked) internet hoax a few years ago. That said, the company’s acquisition by Bayer is worth further consideration. It’s a major move toward further consolidation of the agricultural industry and might just be the link between agriculture and pharma that turns “corporate cannabis” from plausible to inevitable.

Consequences for the Cannabis Industry

Journalist Steve Davis discussed the potential consequences of the Bayer-Monsanto acquisition with Straumeitis. In a 2016 article for Big Buds Magazine (“a sort of Huffington Post for the medical marijuana growers community”), Davis writes:

The corporate interests and immense political power of Bayer, Monsanto, and Scotts Miracle-Gro, enforced by the World Trade Organization and international patent law, could result in corporate ownership of marijuana seed stock, prohibition of cannabis growers producing their own strains, GMO marijuana, and decrease in the number of cannabis strains available.

Straumieitis suspects that the corporate plan is to genetically modify marijuana, establish patented GMO marijuana seeds and strains in the marketplace, and then use patent and trademark enforcement to attack marijuana seed breeders and rob us of our seeds.

This is the exact model Monsanto has used to attack farmers worldwide, Straumietis says.…The corporate goal is to ban growing your own cannabis so you’ll be forced to buy “medical products” such as Sativex.

Through conversations with various intellectual property experts, Vice News extensively explored this possibility in its 2016 article "What a Looming Patent War Could Mean for the Future of the Marijuana Industry." According to Hilary Bricken, lawyer and chair of the Canna Law Group, marijuana farmers are most wary of corporate competition (as opposed to criminal prosecution). “These people aren’t worried about the Department of Justice anymore,” she said. “Now they’re worried about Monsanto.”

Patenting Prevention as an Act of Protection

Marijuana is federally illegal in the United States but legal at the state level in over half of the country. (This is covered more extensively in our first post, "Cannabis: IP Issues in a Budding U.S. Industry.") Its illegal status is likely one of the only obstacles currently preventing major corporations from entering such a fast-growing industry—one projected to reach as much as $47.3 billion in North America by 2027.

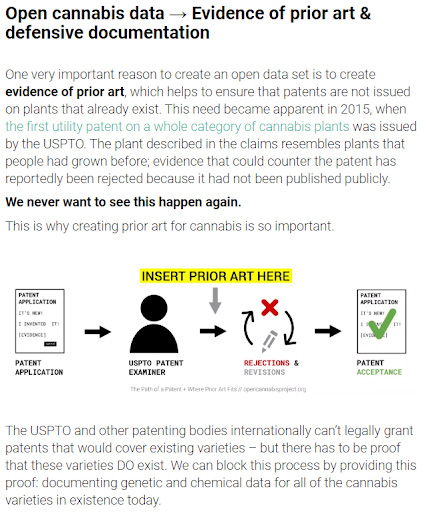

To prevent big companies from entering the industry if and when federal legalization does happen, some are intentionally adding proprietary cannabis information to the public domain. Patents cannot be granted for plants that already exist. Publicly published cannabis plant data essentially act as evidence that can block the patenting process, as explained below.

Source: The Open Cannabis Project

The Open Cannabis Project (OCP) is a nonprofit organization that is building an open-source repository of genetic data of existing cannabis strains, in an attempt to make strains both publicly available and unpatentable. OCP states:

Decades of careful stewardship and breeding have made cannabis into one of the most varied, interesting and powerful plants in the world. The growing wave of legalization—and the intellectual property competition that comes with it—may have the unintended consequence of narrowing and restricting this diversity.

OCP is building a transparent and open source repository of cannabis data that will one day grow into an archival record of all existing cannabis varieties. This documentation effort is a critical step in ensuring that these plants remain available to all, unrestricted by commercialization or patenting, free for anyone to grow and sell.

OCP hopes that documenting cannabis plants will help to protect cannabis biodiversity and keep the marijuana industry “culturally and economically diverse.”

Some think the cannabis industry will end up looking like the beer market—dominated by several large mass distributors, with small craft companies putting out high-quality, artisanal products. In a recently released report on cannabis in Canada, Deloitte even stated that “recreational [marijuana] consumption will eventually become normalized and mainstream, eliciting about as much reaction as having a pint of craft beer.” Could Bayer become the Anheuser-Busch of the cannabis sector? Only time will tell.

About the author: Julia Justusson

As a ktMINE research analyst, Julia Justusson processes and examines intellectual property daily. Interested in tracking innovation across various fields through IP, she uses ktMINE to identify IP patterns that can provide insight into a company’s strategy and industry trends.